-

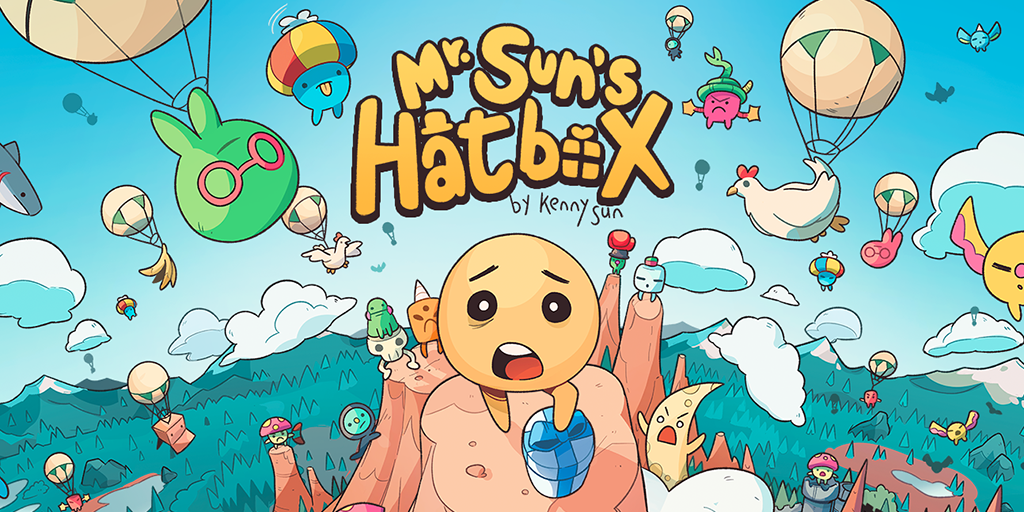

My Experience Pitching Mr. Sun’s Hatbox to Publishers

It’s almost been a year since I released Mr. Sun’s Hatbox on Steam and Switch! I’m really proud of how it turned out, I learned a lot from my time working on it. Probably the most important part of the process was pitching to publishers, which I’d never successfully done before. I made a few mistakes along the way but in the end signed a deal I’m happy with. I’ve decided to share some details about my experience doing that, hopefully it’s helpful to others in a similar position. I’m including actual deal terms and dollar amounts that I’ve seen, it’s pretty rare to see real-life numbers and I think it’s valuable information worth sharing.

In October 2021, after I’d been working on the game for over 2 years, I decided I wanted to find a publisher to take on some of the risk of making this huge game. Here is the pitch deck I put together that ended up getting me a deal with Raw Fury.

I started sending out my pitch deck and build by email around the end of November 2021, asking for $84k in funding to cover my expenses for the next 17 months of development ($6k a month). Turns out that’s a bad time of year to pitch to publishers, since many of them close for the December holidays. At that point I’d only sent it around to my top 5 choices for publisher, which included Raw Fury. I got no’s from three of them and Raw Fury didn’t even respond (turns out my email went into their spam folder). But, I did get some initial interest from one publisher. After some back and forth and a lot of waiting, they sent me their terms in February 2022.

Offer #1

- $84k development budget

- $215k marketing budget

- $220k budget for porting to Switch, Playstation, and XBox, QA, and localization

- 0% revenue share until they recoup their expenses (up to $521k)

- 50% revenue share after they recoup their expenses

At first I was pretty excited. At this point none of my games had made even close to $84k, so I would’ve been happy just to get that amount. But, the estimated budgets for marketing and porting seemed really high to me, so I asked some other developers for their thoughts. In these discussions, two valuable pieces of advice came up:

- I was asking for too little money – Publishers have so much money and even at the indie scale are used to budgets of multiple hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars. Any extra amount would mean very little to them but a lot to me.

- I should reach out to more publishers – I’d initially only sent it to my top 5 since I didn’t want to “waste” time talking to publishers that I wasn’t interested in working with. But, since only one had expressed any interest, I was in a pretty tough negotiating position.

So, I upped my development budget to $116k ($8k a month) and sent the game around to 25 more publishers. I also DM’ed a scout from Raw Fury who I’d met a while ago while showing Circa Infinity at PAX in 2015 to ask if they’d gotten my pitch. By April 2022 I’d received 3 more offers. Here are the terms that they each offered:

Offer #2

- $140k development budget ($24k was added so I could do the Switch port myself)

- $80k marketing budget

- $40k budget for QA and localization

- 30% revenue share until they recoup their expenses (up to ~$371k)

- 60% revenue share after they recoup their expenses

Offer #3

- $116k development budget

- $50k marketing budget

- 30% revenue share until they recoup their expenses (up to ~$237k not counting QA, porting, and localization)

- 70% revenue share after they recoup their expenses

Offer #4 (Raw Fury)

- Much higher budgets for development, marketing, and other services (specifics under NDA)

- 0% revenue share until they recoup their expenses with a 15% markup on the development budget

- 50% revenue share after recoup

- The contract I signed was basically the same as the one they posted publicly

My first concern when talking to Raw Fury was that I knew that their terms were pretty aggressive. The thought of them taking 50% revenue share from a game I’d worked on for years on my own was a tough pill to swallow. I asked them they could could adjust their revenue share to be a bit more favorable to me, but they were adamant that they basically never make any changes to their terms (personally I’m not really a fan of this practice as it’s disadvantageous to smaller devs). When I mentioned that I would probably only accept those terms if I got more money up front, citing my other offers with better terms, they offered to drastically increase my budget to make up for it.

Raw Fury also adds a 15% markup on the development budget when calculating the recoup point. For example, if they give me $100k, the game would have to make $115k before I start receiving revenue share. I think the markup is partially meant to discourage developers from taking more budget than they need. But even at 15%, it is always more advantageous (at least financially) for the developer to take as much money as they can up front. Especially since they don’t offer better revenue share terms. If you’re pitching to Raw Fury, I would recommend adding at least a 20-30% margin to your development budget (which should already have a good amount of contingency in it) to offset the markup.

I tried to use Raw Fury’s offer to negotiate with the other interested publishers, but none of them would improve their deal. One even ended up rescinding their offer when I tried to negotiate (Offer #1). So, even though they had the worst revenue share terms, I decided to go with Raw Fury. Since I’m a fairly risk averse person, the guaranteed money up front was a big deciding factor. The extra funding meant I’d be getting the equivalent of a decent salary for my 3-4 years of work. It would also give me a decent amount of runway, enough to make another game of a similar size. I went into this decision with tempered expectations on how well the game would do. I didn’t expect it to make make much more than the recoup point, if at all, so the post-recoup revenue share wasn’t a big factor for me. In the off-chance the game does become a huge hit, Raw Fury would have to perform 20-50% better than the smaller publishers for me to make the same amount of money, which I thought would be within the realm of possibility. As of January 2024 the game has made a bit over $140k in net revenue, so taking the extra budget in exchange for worse revenue share was definitely the right call, as it’s unlikely that the game will recoup its expenses. In the end, I’m happy with the decision I made and feel incredibly fortunate that they took a chance on my silly game.

-

Mr. Sun’s Hatbox is Out Now!

-

GameDeveloper.com Road to IGF Interview

The game I’m currently working on, Mr. Sun’s Hatbox, was recently nominated for an IGF award in Excellence in Design! What an honor! As part of that, they conduct interviews with all of the nominees. I spent quite a bit of time writing my answers up so I’ve reposted it below.

Who are you, and what was your role in developing Mr. Sun’s Hatbox?

I’m Kenny Sun, the solo developer behind Mr. Sun’s Hatbox. I worked on almost every part of the game on my own including design, programming, art, animation, sound design, and music.

What’s your background in making games?

I first started making games in high school and released a few flash games on Newgrounds. Then, in college, I took a few game design classes and made a couple of Game Maker games on my own. One of them, Circa Infinity, got some attention and helped me get a job in the industry as a programmer at Harmonix. I worked there for a few years while still making my own games on the weekends. Eventually, those projects made enough to cover my living expenses so I quit in 2018 to try making indie games full-time. I’ve been doing that ever since, aside from a year-long break when I had the chance to work as a programmer on Return to Monkey Island.

How did you come up with the concept for Mr. Sun’s Hatbox?

I initially came up with the idea for the game in 2015 after playing Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain. I really enjoyed the Fulton recovery system where you attach balloons to stunned enemies to lift them into the air and kidnap them. So, I stole that idea and combined it with elements from another favorite game of mine, Spelunky.

I started to prototype the game in 2016, but quickly abandoned it after realizing how huge of a project it’d be given my limited free time (I had a full-time job back then). I forgot about it for a while, but then on my birthday in 2019, my housemate suggested that I should take the day off from the project I’d been working on and start something new as a treat to myself, so I decided to take another stab at the idea. I’ve been working on it ever since.

What development tools were used to build your game?

I used Unity as the engine, FMOD for audio, Aseprite to make the pixel art, and Logic to make the music.

You describe the game as a ‘slapstick roguelite platformer’. What drew you to bring slapstick into such a stressful, tense genre?

I actually didn’t seek to make a funny game when I first started developing it. I’d only started leaning into the humor after I noticed a lot of slapstick moments during playtests. As I added more and more funny elements, the humor became the identity of the game.

Mr. Sun’s Hatbox features a ridiculous array of tools and hats for players to work with. What thoughts go into designing weapons around silliness, slapstick, and humor?

There were a few approaches I took to coming up with ideas for items:

- Steal ideas from other games and add a funny twist. For example, I stole the boomerang from Spelunky and made it so you can’t catch it when it returns to you, it’ll just knock you out.

- Start with a funny visual idea and try to determine how it would work mechanically. A lot of the animal hats started like this, like the frog or snake hat.

- Start with a mechanic and think of items that would plausibly fit it in a funny way. For example, I had the idea for a gun whose bullets would bounce around the level. Turning it into a ping pong paddle that shot bouncing ping pong balls elevated the idea into something funny.

- Lean into the kinetic aspect of the game. I noticed that a lot of the game’s funny moments came from characters being bounced around the screen, so I added an array of hats that would launch characters in different directions.

- Add items that have no in-game benefit. Some of my favorite items are things like the blindfold, which literally covers your vision if you put it on. Or the headphones that just play different music when you wear them. Even if there’s no point to using them, they create a funny moment of surprise the first time you encounter them.

- Get ideas from friends. Many of the game’s best ideas are from playtesters and pals.

What challenges do you face when you have so many silly effects your weapons and tools can cause?

Readability can be a challenge, especially when using low-resolution pixel art with my limited art skills. One way I addressed it was to show a text popup whenever you pick up an item that tells you what it is. Even with that, there are still moments that happen too quickly for someone new to the game to parse. I didn’t really do anything more to address that though. It’s kind of something that you just get used to as you play the game.

Can you tell us a bit about how you came up with the art style? What made the look of the game feel right for an experience focused on silliness?

Since I’m fairly inexperienced as a pixel artist, I don’t really have the skill level to define and execute a unique art style. A lot of what defined the style was actually the tutorials I watched to get better at pixel art. Pixel Pete’s tutorials were the basis on which the style for the items came from, while AdamCYounis’s tutorials helped me figure out how to make the background tiles and buildings.

What thoughts went into the design of the base, and how players can build/expand on it? What do you feel this added to the game?

The actual structure of the base was defined very early on, with it just being a simple 4×3 grid of rooms. I kind of went with the simplest idea and stuck with it because nobody complained about it. I guess one thing that did change is that, earlier on, you didn’t even have to place rooms; they’d automatically get built as you progressed in the game. Later on, I updated it so you had to manually pick where each room would go. There is no mechanical benefit to placing a room in any specific place, but it added a small bit of customizability to an otherwise invariable part of the game.

Did you work to infuse that same silliness into the rooms and what they do?

I don’t think I actually spent that much effort trying to make the base management side of things silly. There’s some dark humor in there; one of the rooms lets you brainwash enemies you capture into joining your side. And another room that lets you perform lab experiments on your units to extract and instill personality traits. But even then, I never went out of my way to make those bits funny, they were just the most straightforward way to translate those mechanics into something narratively feasible. I guess the only intentional humor in the base management side is the narrative bit. Why is this delivery company digging a huge base of operations under their client’s house? Poor Mr. Sun.

As a developer, how does it feel to work on a game focused on humor and making the player chuckle? Does it feel different in some ways compared to development of other games?

It’s nice because it’s easier to tell if you’ve done a good job by seeing if people laugh while they play. And it’s always satisfying when I’m testing out an item and laugh out loud at something unexpected happening. On the design side, there’s a lot less pressure to make the game feel balanced than a more self-serious game. But otherwise, it mostly feels the same as making any other type of game.